With all the promise that educational technology holds, several pitfalls are always on the minds of educators. The top two issues that commonly come up in my talks with educators are the technology (Internet, hardware, devices, apps) not working or off-task behavior on the part of students. While there are some serious challenges that can derail any lesson, there are some strategic ways to mitigate them ground in instructional design. Here are some of the most commonly implemented strategies, which I will describe in more detail in this post.

It is tough to argue the fact that many learners will quickly go off and remain off task if a classroom is not managed effectively. The key above all else is to build positive relationships with kids. One great way to do this is to co-construct rules with them as well as ramifications if they are not followed or broken. Addressing issues immediately as they arise, re-directing adverse behaviors, and utilizing positive reinforcement at opportune times all aid in creating a classroom conducive to learning.

Pedagogically Sound Lessons

If you are a reader of this blog, then you know that this is one area that I focus on extensively with my writing. Instructional design is one of the best deterrents to off-task behavior. If a student, or adult for that matter, is bored, then we better accept what might happen. It is critical to get kids so immersed in their learning that they don’t think about surfing the web aimlessly, texting their friends, or accessing social media. Sound pedagogy consists of effective instructional strategies that involve all learners, a focus on higher-order thinking skills, scaffolding techniques, construction of new knowledge, and relevant application of thinking. Mitigating edtech related issues rests on authentically engaging as many learners as possible.

Monitoring

If kids are given a task to complete on a device, whether independently, in cooperative groups, or as a part of many different blended learning models, sitting or standing in the same place in the front of the room might lead to unintended consequences. During situations like this is when I commonly observe kids focused on anything but the learning at hand. It is vital to move about the room to not only look at what is on a learner’s screen but to also be in a position to either re-direct any off-task behavior or provide needed guidance.

Accountability for learning

When I say accountability, I am not talking about grades. I can go on and on about the fact that many grading practices are outdated, ineffective, and do not adequately reflect what a student has learned. What I am referring to are specific strategies that keep kids focused on the task at hand while ensuring that his or her part in the learning process is completed. Some ways to accomplish this include assigning equitable roles to each individual student in a cooperative group, handing in an assignment, developing performance tasks where a product is created, or using digital tools in a way where every student can report out using his/her real name.

Feedback

Continuous feedback is essential on so many levels. It helps to justify a grade, establishes criteria for improvement, provides motivation for the next assessment, reinforces good work, and serves a catalyst for reflection. Blended learning strategies lend themselves to providing continuous feedback during class time, which in turn helps to keep kids on task. Keep in mind that it doesn’t have to be just a teacher to teacher pathway. Creating opportunities for learners to give each other peer feedback is just as valuable.

Assessment

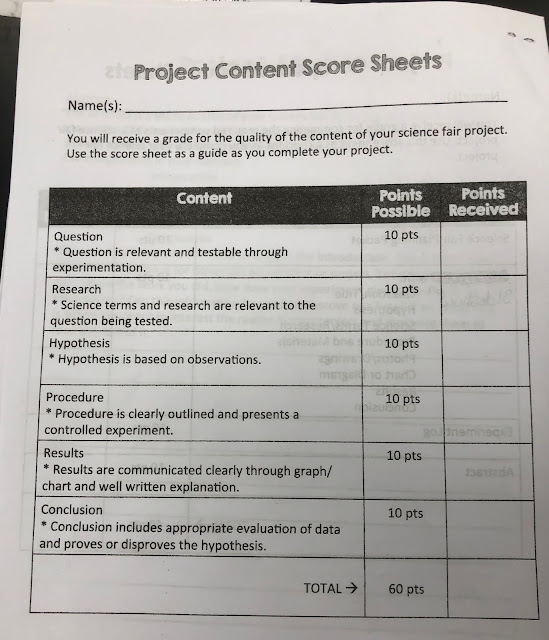

I would be remised if I didn’t include this strategy. Assessment determines whether learning occurred, what learning occurred, and if the learning relates to stated targets, standards, and objectives. For many learners knowing that they will ultimately be assessed based on the activities and tasks they have engaged in increases attentive behavior. A variety of strategies beyond traditional tests can be used, such as performance-based activities, portfolios, and rubrics.

The reality is that no matter how well you implement the above strategies, the chances are that a few students might still go off task. I am a realist. It is extremely challenging, no matter how great the lesson is, to engage each and every learner. What I do know is that the strategies listed above will help to mitigate common issues that arise when technology is utilized in the classroom. So, what did I miss? Please share any other successful strategies that you have successfully implemented.

- Classroom Management

- Pedagogically sound lessons

- Monitoring

- Accountability for learning

- Feedback

- Assessment

It is tough to argue the fact that many learners will quickly go off and remain off task if a classroom is not managed effectively. The key above all else is to build positive relationships with kids. One great way to do this is to co-construct rules with them as well as ramifications if they are not followed or broken. Addressing issues immediately as they arise, re-directing adverse behaviors, and utilizing positive reinforcement at opportune times all aid in creating a classroom conducive to learning.

Pedagogically Sound Lessons

If you are a reader of this blog, then you know that this is one area that I focus on extensively with my writing. Instructional design is one of the best deterrents to off-task behavior. If a student, or adult for that matter, is bored, then we better accept what might happen. It is critical to get kids so immersed in their learning that they don’t think about surfing the web aimlessly, texting their friends, or accessing social media. Sound pedagogy consists of effective instructional strategies that involve all learners, a focus on higher-order thinking skills, scaffolding techniques, construction of new knowledge, and relevant application of thinking. Mitigating edtech related issues rests on authentically engaging as many learners as possible.

Monitoring

If kids are given a task to complete on a device, whether independently, in cooperative groups, or as a part of many different blended learning models, sitting or standing in the same place in the front of the room might lead to unintended consequences. During situations like this is when I commonly observe kids focused on anything but the learning at hand. It is vital to move about the room to not only look at what is on a learner’s screen but to also be in a position to either re-direct any off-task behavior or provide needed guidance.

Accountability for learning

When I say accountability, I am not talking about grades. I can go on and on about the fact that many grading practices are outdated, ineffective, and do not adequately reflect what a student has learned. What I am referring to are specific strategies that keep kids focused on the task at hand while ensuring that his or her part in the learning process is completed. Some ways to accomplish this include assigning equitable roles to each individual student in a cooperative group, handing in an assignment, developing performance tasks where a product is created, or using digital tools in a way where every student can report out using his/her real name.

Feedback

Continuous feedback is essential on so many levels. It helps to justify a grade, establishes criteria for improvement, provides motivation for the next assessment, reinforces good work, and serves a catalyst for reflection. Blended learning strategies lend themselves to providing continuous feedback during class time, which in turn helps to keep kids on task. Keep in mind that it doesn’t have to be just a teacher to teacher pathway. Creating opportunities for learners to give each other peer feedback is just as valuable.

Assessment

I would be remised if I didn’t include this strategy. Assessment determines whether learning occurred, what learning occurred, and if the learning relates to stated targets, standards, and objectives. For many learners knowing that they will ultimately be assessed based on the activities and tasks they have engaged in increases attentive behavior. A variety of strategies beyond traditional tests can be used, such as performance-based activities, portfolios, and rubrics.

The reality is that no matter how well you implement the above strategies, the chances are that a few students might still go off task. I am a realist. It is extremely challenging, no matter how great the lesson is, to engage each and every learner. What I do know is that the strategies listed above will help to mitigate common issues that arise when technology is utilized in the classroom. So, what did I miss? Please share any other successful strategies that you have successfully implemented.